THE

SOUND OF SILK AND BAMBOO

By

Wei Li

>>

Chinese Music is a broad concept, which encompasses a wide spectrum

of genres and traditions derived from a number of different ethnic

groups. Musical traditions that are most familiar to Westerners,

such as Peking opera or Cantonese music, are just two examples of

China’s 56 ethnic cultural traditions. Since the Han is by far the

largest ethnic group in China constituting nearly 96% of the total

population, it is the musical heritage of the Han that is known to

the world as Chinese music. This musical heritage includes many

different traditions, one of which is instrumental music, which in

turn comprises a variety of regional solo and ensemble music.

The

ancient Chinese divided musical instruments into eight categories

according to the materials used in their construction known as bayin

or "eight tones." They are metal (jin), stone (shi), silk (si), bamboo (zhu),

gourd (pao), clay (tu), membrane (ge), and wood (mu). While big ensembles consisting of all the "eight tones" exist

only in ritual contexts (such as Confucian ritual music), ensembles

combining three to six different types of musical instruments are

more common in modern music practice.

Instruments such as the bianqing

(stone-chime, "stone"), bianzhong (bell-chime, "metal"),

and zhu (wooden box, "wood") are rarely heard today since they were used with

imperial court music and ritual.

However, instruments associated with folk music such as the

erhu (a two-stringed fiddle), dizi (a transverse bamboo flute), pipa

(a pear-shaped plucked lute) and zheng (a 16-or 21-string plucked

zither), have gained increasing popularity in modern times.

These

instruments fall into either the "silk" or "bamboo" category (e.g.,

the dizi is a bamboo aerophone, whereas the pipa, erhu, and zheng

are silk-stringed chordophones).

Combining these two has yielded one of the most popular

Chinese music genres – sizhu or silk and bamboo music.

Sizhu is comparable to Western chamber music and is commonly

heard in teahouses, guild houses, or cultural centers where casual

and informal atmospheres are the norm.

Comprising mainly but not exclusively stringed instruments

and bamboo flutes, the sizhu uses various two-string fiddles of the

huqin family, a variety of plucked lutes, bamboo flutes, sheng (a

mouth organ), yangqin (a hammered dulcimer), and a number of

percussion instruments. Four

distinct sizhu traditions can be identified by their origins:

1) Shanghai centered Jiangnan sizhu ("silk and bamboo of

southern river"); 2) Cantonese music; 3) Nanqu or Nanyin which

prevailed in Fujian Province; and 4) Chaozhou sixian ("Chaozhou silk

and string") from the Chaozhou and Shantou regions of Guangdong

Province. While each

sizhu tradition is characterized by its instrumentation and timbral

coloring peculiar to its local origin, they are all heterophonic in

their simultaneous use of elaborately modified versions of the same

melody by two or more performers.

Improvisation and ability to alter linear rendition are

highly valued among traditional sizhu performers as it is these

subtle changes that provide much of the vitality of the music.

Another

major traditional ensemble music genre is called chuida or "wind and

percussion". Unlike

sizhu, most chuida music is played outdoors and is sometimes

processional. About

five major geographically divided chuida musical traditions can be

found in Mainland China: three

in the south (Zhedong luogu, Sunan chuida, and Chaozhou daluo) and

two in the north (Hebei chuige and Jinbei guyue).

They tend to use loud instruments including various gongs,

cymbals, drums, suona and guanzi (multiple reed oboes), and bamboo

flutes. In some areas string instruments are also added; these

include the huqin, erxian (both 2-strubged fiddles), pipa and

sanxian (plucked lutes). Rooted

in rural areas, chuida is closely tied to people’s day-to-day

life, and performed on important occasions, such as marriage,

funeral, religious rites, and folk festivals.

Beginning

in this century, the solo aspect of Chinese instrumental music has

rapidly developed in Han musical culture due largely to Western

music influence, instrument refinement and the rise of professional

orchestras and ensembles. Once

considered the domain of folk music, instruments like the pipa, erhu,

zheng, and dizi are now systematically taught in conservatories and

have become favorite solo instruments for new compositions.

Inventing new playing techniques and pursuing virtuosity

became a trend among professional musicians who encouraged composers

to write grander, more difficult pieces for solo instruments.

Western influence has also played a big role in shaping

modern Chinese solo musical styles.

Idioms, such as the symphony and concerto, and concepts, such

as harmony and chromaticism, have not only been adapted into music

composition and concert performance but also influenced instrument

making. A large scale "instrument reform" campaign undertaken from

the 1950s to ‘70s has yielded a large crop of reformed or newly

designed instruments that have increased the dynamic and octave

range by adding extra frets or strings to traditional instruments.

Steps were taken in chromatic or equal temperament tuning

with some conventionally pentatonically tuned instruments such as

the yangqin (hammered dulcimer), zheng (board zither), and sheng

(mouth organ). These

modified instruments are more suitable for the 20th-century

concert hall music (guoyue) characterized by large ensembles

incorporating Western harmony and orchestration but grounded in

traditional Chinese pentatonic structure.

Today a

handful of Chinese musical instruments remain almost intact and one

such example is the qin, a seven-string plucked zither.

The qin is one of the oldest Chinese music instruments and

has long been associated with literati and Confucianists.

The ancient ideology of qin, highlighting the educational and

meditative functions of music, closely parallels those of ancient

Greek music and the Indian Brahmanic tradition.

Music performance is ideally not to be considered a

profession, but rather an avocation; one practices music for its

qualities of illumination or self-cultivation, not for remuneration.

Since musical knowledge is considered a scholarly activity in

qin music context, the qin player usually spends considerable time

studying music theory and exchanging his thoughts with others in a

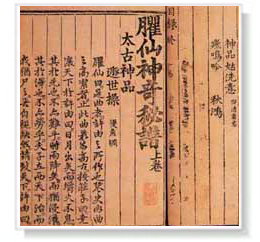

qin ‘club’. This

will eventually benefit the performer’s ability to dapu (literally

"striking notation"), unique process of revealing ancient qin music

through the performer’s creative interpretation based on ancient

qin tablature. Nowadays

the qin is not as popular as the erhu, dizi, or zheng, it

nonetheless remains a musical symbol of Chinese literati culture.

Despite

the fact that the "traditional" element is overshadowed by its "modern"

aspect in contemporary Chinese solo music making, efforts in

preservation and revitalization of traditional solo music have been

undertaken in recent years among Chinese music communities in China,

Taiwan, Hong Kong and overseas. Beginning in the late ‘70s, government-supported

organizations in Mainland China launched a "national cultural

heritage rescue" campaign in which systematic documentation of major

music genres and their representative performers, especially the

older generations became the top priority.

In China, much of the solo music prior to the ‘60s is

stylistically divided based on region. Each established school is distinguished by its own

repertoire and instrumental techniques.

Hence, while the Shandong Zheng School of northern China

specializes in thumb plucking, the Chaozhou school of Guandong

Province is acknowledged for the use of metal picks.

Traditional pipa music can be identified not only by whether

it belongs to wenqu ("civil") or wuqu ("military"), but also by its

rendition as determined by stylistic affiliation.

A performance by an accomplished musician who has a strong

lineage reveals much of the peculiar characteristics unique to the

particular school to which he/she is associated.

Although the modern conservatory system has more readily

available resources to learn traditional music performance,

apprenticeship with masters of established stylistic schools is

still highly valued among the musical community.

<<read

another article>>

home :: email

|